[ad_1]

An entry in the first edition of the Oriental Herald and Colonial Intelligencer by Barbie, published in 1838, gives some fascinating insights into the early years of Calcutta and its relation to ice, a desirable product in colonial India. There is a fair amount of literature on how the colonial powers in the Indian subcontinent dealt with the oppressive temperatures they considered. While some methods involved climbing hill stations to escape the heat, by the 19th century, there was another new addition: ice.

In the Indian subcontinent, the local use of ice was not completely known. About three centuries before the British enchanted Calcutta with ice, Babur, the first Mughal emperor, used his vast resources to haul ice on elephants and on horseback from Kashmir to the capital at Delhi.

There is some archival documentation to suggest that the British tried to emulate the Mughal practice of hauling ice out of Kashmir, but the expense involved led East India Company officials to drop those plans and, instead, focus on American ice.

There was more to the British East India Company’s inability to bring ice from Kashmir and the wider Himalayas to Calcutta, says Tathagata Niyogi, historian and co-founder of Immersive Trails. “Bengals didn’t necessarily have that access because the high Himalayas were under the kingdom of Kochibahar, Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim. So the Dutch started producing something in Bengal called ‘Hooghly ice’. This was basically watery slurry made in very deep pits in Chinsurah and Hooghly. Of course, this slush wasn’t drinkable by itself, and it was imported to other European colonies to cool the drinks by putting the slush in a large cup, and placing smaller cups containing the drinks inside the slush,” Newgy says.

Native American ice shipped to Calcutta meant the drinks could be enjoyed the way the colonists were accustomed to.

When the ice first arrived at the docks of Calcutta on a ship called “The Clipper Tuscany” in September 1833 from the American city of Boston, the colonial inhabitants of the city were overjoyed. The packed ice had survived a four-month long voyage across many seas, and the 100 tons of ice that eventually reached the town’s colonial inhabitants was such a monumental event that the first British Governor-General of Bengal, William Bentinck, paid tribute to him. The ship’s crew, especially the man in charge of the valuable cargo, William C. Rogers.

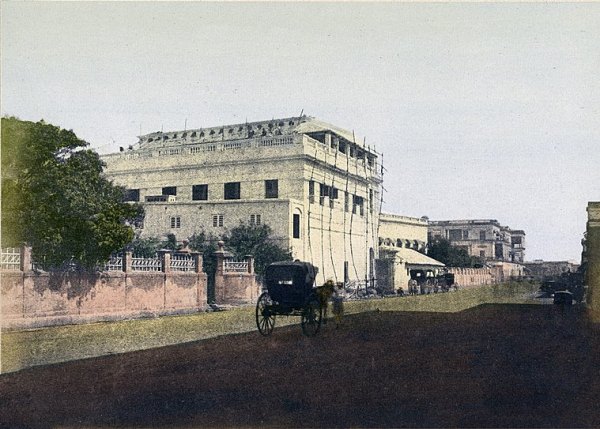

Hand-coloured print of Ice House, Calcutta, from the Fiebig Collection: Views of Calcutta and its Surroundings, Taken by Frederick Fiebig in 1851. The Ice Houses at Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras were built by Frederick Tudor, a Boston merchant, who first brought ice to India in The year 1833 on a ship called “The Clipper Tuscany”. (Image source: British Library)

Hand-coloured print of Ice House, Calcutta, from the Fiebig Collection: Views of Calcutta and its Surroundings, Taken by Frederick Fiebig in 1851. The Ice Houses at Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras were built by Frederick Tudor, a Boston merchant, who first brought ice to India in The year 1833 on a ship called “The Clipper Tuscany”. (Image source: British Library)

The Oriental Herald and Colonial Intelligencer states that the first ice house in Bengal cost Rs. 10,500, an astronomical amount of money at the time, and was used to store “American Ice”. but the ice-house did not seem to work as well as might have been expected, and ‘a vigorous appeal was made to the public for subscriptions for the erection of one more. This appeal was rather habitual, and particularly to the ladies, who replied to it by subscription at Rs. 1452; he advanced gentlemen with Rs. 6,435, a total of Rs. 7,959; but listings are still open,” the entry says.

Although a luxury good in 19th-century Bengal, ice was not quite accessible at four ans per pound, but was only consumed by the British and other Europeans in the city.

It is not clear when the Tudor Ice Company was created by Frederick Tudor, an American trader who built a large portion of his fortune on the ice trade, but for nearly two decades, he dominated the trade. “The Tudor Ice Company founded by Frederick Tudor in Boston was the only player importing ice into India and Calcutta all the way from the United States in their custom-made ships. Locally in Calcutta, and other coastal colonial cities, ice houses were erected,” Newgy says.

In his paper “American Ice Harvests; A Historical Study in Technology, 1800-1918,” author Richard O. Cummings states that the ice that the Tudors transported over seas to Calcutta was harvested from the icy rivers, ponds, and streams of Massachusetts during cold New England winters.

The Journal of the Asiatic Society offers some insights into how Tudor and his fellow ice traders harvested ice. The snow harvesting process involved cutting blocks of ice frozen on bodies of water. In the early years of the trade, it was carried out by men using axes, chisels, and other similar tools. But it was soon replaced by a horse-drawn vehicle.

One of the greatest challenges was perfecting the art of storing ice, which in the early years of the trade tended to melt in the absence of proper storage facilities in America itself, even before it was loaded onto ships. By 1810 Tudor had figured out a way to store ice in special ice bunkers, with the first built in 1810 in Havana, despite the US trade embargo on Cuba.

The Americans remained the sole player in importing ice into the Indian subcontinent, but they appointed local agents in the cities in which they operated for logistical reasons. In Calcutta, the Akror Dutta family of Bobazar was their agent in Calcutta, says Newgi.

Photograph of an ice house in Madras (Chennai), Tamil Nadu, taken in 1851 by Frederick Vibeg. The image is one of a series of hand-coloured salt prints. The ice house was standing by the road on the foreshore next to Marina Beach. It is a beautiful circular building with Ionic columns and a pineapple finial. The Ice House was erected in 1842 to store large blocks of ice which were imported from America by the Tudor Ice Company, which was formed in 1840. After the establishment of local ice mills, it was later converted into a home for Brahmin widows and is now a hostel for the well-known Lady Willingdon Training College In the name of Vivekananda House. (Image source: British Library)

Photograph of an ice house in Madras (Chennai), Tamil Nadu, taken in 1851 by Frederick Vibeg. The image is one of a series of hand-coloured salt prints. The ice house was standing by the road on the foreshore next to Marina Beach. It is a beautiful circular building with Ionic columns and a pineapple finial. The Ice House was erected in 1842 to store large blocks of ice which were imported from America by the Tudor Ice Company, which was formed in 1840. After the establishment of local ice mills, it was later converted into a home for Brahmin widows and is now a hostel for the well-known Lady Willingdon Training College In the name of Vivekananda House. (Image source: British Library)

Dutta was originally a slush trader based in Bengal, selling inferior local slush produced in Hooghly, with the arrival of American ice, it probably made sense that Dutta would be in a privileged position to trade in the superior version of the product he had to sell originally. The business made Dutta and other merchants like him very wealthy. Ice houses were built not only in Calcutta but also in other parts of the Indian subcontinent where the British East India Company operated, such as Madras and Bombay.

After cotton, by 1847 ice had become the second most important trade commodity between America and the Indian subcontinent. In addition to being consumed by the privileged colonial residents, imported ice was also used for storage. When the first shipment of snow arrived, it was sent out to keep a large shipment of American apples fresh. So it was used here for similar reasons – mainly to cool drinks at parties. Having snow in the house was a matter of privilege and of showing one’s wealth. Often in September and October, the ice import season, tons of iced champagne dinners are organized by Calcutta’s elite. Ice was very expensive for the general public to access, and it was very rare that one would need a prescription to get access to some ice, if you didn’t know the right people,” Newgy says.

“The East India Company allowed tax-free imports of ice for the Tudor Ice Company, but this privilege was withdrawn in 1853 by executive order of Governor-General Lord Dalhousie,” says Newgy.

Among the Indians, their relationship with the ice was somewhat complicated. At first, there were mixed feelings. Dockers were the first Indians in Bengal to encounter ice. They were skeptical about (this thing) that gave you goosebumps to the touch but also smoked. So they thought the ice was a cursed item, and demanded more money to unload it from the ships that brought them. In general, Indian elites, who could afford it, considered it a curiosity and a privilege,” says Newgi.

In her 2009 article Food Culture in Colonial Bengal, author Utsa Rai writes that in colonial Bengal, “everything that was new was considered a caste taboo.” Mahendranath Datta, brother of famous religious preacher Vivekananda, writes for example: “My younger uncle used to Buying snow and bringing it home covered with a blanket. This ice must be preserved with sawdust. This was a strange thing. It was never consumed by orthodox Hindus. In our house, widows also abstained from it. We tried it, but in a sneaky way. Maybe that’s why we didn’t lose our caste so quickly.” .

Just under two decades later, the US ice trade took an even bigger hit. Colonial powers discovered new, modern ways of making ice, phasing out the need for American ice. American ice became so redundant that the British built an ice plant in Calcutta in 1878 and demolished the city’s old ice house in 1882. The fate of the ice houses in Madras and Bombay followed a similar course, and by the late 1880s these establishments too were being pulled down .

[ad_2]