[ad_1]

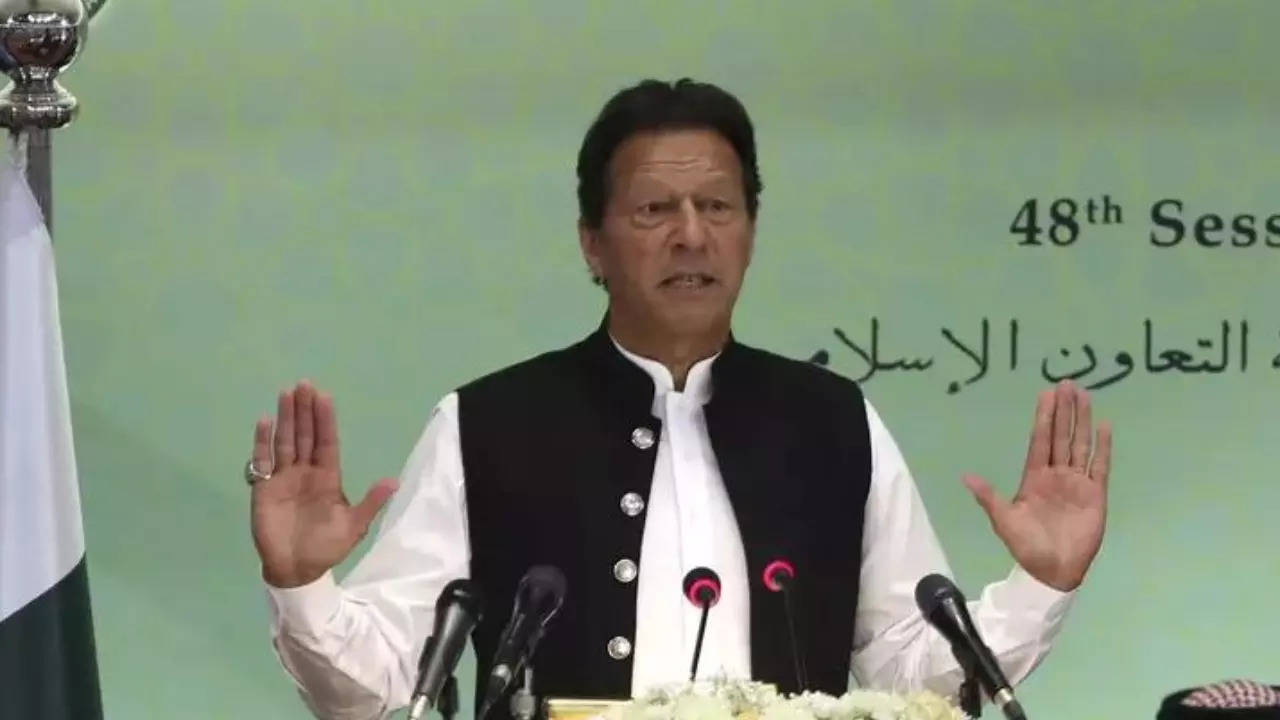

Pakistan’s former prime minister, Imran Khan, the cricket hero-turned-politician who was arrested on Tuesday, has rallied public support amid a decades-high and crippling inflation. economic slowdown before he was overthrown last year.

Since then, the 70-year-old has shown no sign of slowing down, even after he was injured in an attack in November on his convoy as he led a protest march to Islamabad to demand early general elections.

Khan avoided for several months Arrest In a number of cases registered against him, which include charges of inciting crowds to violence. Mass protests erupted against previous attempts to arrest him.

Khan was ousted from the premiership in April last year amid public frustration with soaring inflation, soaring deficits and the endemic corruption he promised to eradicate.

The Supreme Court overturned his decision to dissolve Parliament and his defection from his ruling coalition led to his loss in the vote of no confidence that followed.

That put him among a long list of elected Pakistani prime ministers who have failed to complete their terms – none of them having done so since independence in 1947.

In 2018, the cricket legend who led Pakistan to their only World Cup victory in 1992 rallied the country behind his vision of a corruption-free, prosperous and respected country abroad. But the fame and charisma of the charismatic patriot was not enough.

After being criticized for being under the control of the powerful military establishment, Khan’s ouster came after relations deteriorated between him and the then army chief, General Qamar Javed Bajwa.

The military, which has had a huge role in Pakistan after ruling the country for nearly half of its history and controlling some of its largest economic institutions, said it remains neutral on politics.

zoom

But Khan is once again among the most popular leaders in the country, according to local opinion polls.

His rise to power in 2018 came more than two decades after he first launched his own political party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), or Pakistan Movement for Justice party, in 1996.

Despite his fame and hero status in cricket-obsessed Pakistan, PTI has struggled in the Pakistani political wilderness, winning no other seat than Khan for 17 years.

In 2011, Khan began drawing huge crowds of young Pakistanis disillusioned with endemic corruption, chronic electricity shortages, education crises, and unemployment.

He gained greater support in the following years, as educated Pakistani expatriates quit their jobs to work for his party and pop musicians and actors joined his campaign.

His goal, Khan told supporters in 2018, is to transform Pakistan from a country with “a small group of rich people and a sea of poor people” into “an example of a humane system, a just system, to the world, of what is Islamic”. welfare state”.

That year he triumphed, marking the rare ascent of a sports hero to the top of politics. However, observers warned that his biggest enemy was his rhetoric, which had raised the hopes of his supporters too high.

Playboy reformer

Born in 1952, the son of a civil engineer, Khan grew up with four sisters in a wealthy Pashtun family in Lahore, Pakistan’s second largest city.

After getting an outstanding education, he attended the University of Oxford where he graduated with a BA in Philosophy, Politics and Economics.

As his cricket career blossomed, he developed a reputation as a playboy in London in the late 1970s.

In 1995, he married Jemima Goldsmith, daughter of businessman James Goldsmith. The couple, who had two sons together, divorced in 2004. A second marriage, to TV journalist Reham Nayyar Khan, also ended in divorce.

His third marriage, to Bushra Bibi, a spiritual leader whom Khan knew during his visits to a 13th-century mausoleum in Pakistan, reflected his deep interest in Sufism—a form of Islamic practice that emphasizes spiritual closeness to God.

Once in power, Khan set about his plan to build a “welfare” state modeled after what he said was an ideal system dating back to the Islamic world some 14 centuries ago.

But his anti-corruption campaign has been roundly criticized as a tool for marginalizing political opponents – many of whom have been jailed for corruption.

Pakistani generals also remained powerful and military officers, both retired and active duty, were given responsibility for more than a dozen civilian enterprises.

Since then, the 70-year-old has shown no sign of slowing down, even after he was injured in an attack in November on his convoy as he led a protest march to Islamabad to demand early general elections.

Khan avoided for several months Arrest In a number of cases registered against him, which include charges of inciting crowds to violence. Mass protests erupted against previous attempts to arrest him.

Khan was ousted from the premiership in April last year amid public frustration with soaring inflation, soaring deficits and the endemic corruption he promised to eradicate.

The Supreme Court overturned his decision to dissolve Parliament and his defection from his ruling coalition led to his loss in the vote of no confidence that followed.

That put him among a long list of elected Pakistani prime ministers who have failed to complete their terms – none of them having done so since independence in 1947.

In 2018, the cricket legend who led Pakistan to their only World Cup victory in 1992 rallied the country behind his vision of a corruption-free, prosperous and respected country abroad. But the fame and charisma of the charismatic patriot was not enough.

After being criticized for being under the control of the powerful military establishment, Khan’s ouster came after relations deteriorated between him and the then army chief, General Qamar Javed Bajwa.

The military, which has had a huge role in Pakistan after ruling the country for nearly half of its history and controlling some of its largest economic institutions, said it remains neutral on politics.

zoom

But Khan is once again among the most popular leaders in the country, according to local opinion polls.

His rise to power in 2018 came more than two decades after he first launched his own political party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), or Pakistan Movement for Justice party, in 1996.

Despite his fame and hero status in cricket-obsessed Pakistan, PTI has struggled in the Pakistani political wilderness, winning no other seat than Khan for 17 years.

In 2011, Khan began drawing huge crowds of young Pakistanis disillusioned with endemic corruption, chronic electricity shortages, education crises, and unemployment.

He gained greater support in the following years, as educated Pakistani expatriates quit their jobs to work for his party and pop musicians and actors joined his campaign.

His goal, Khan told supporters in 2018, is to transform Pakistan from a country with “a small group of rich people and a sea of poor people” into “an example of a humane system, a just system, to the world, of what is Islamic”. welfare state”.

That year he triumphed, marking the rare ascent of a sports hero to the top of politics. However, observers warned that his biggest enemy was his rhetoric, which had raised the hopes of his supporters too high.

Playboy reformer

Born in 1952, the son of a civil engineer, Khan grew up with four sisters in a wealthy Pashtun family in Lahore, Pakistan’s second largest city.

After getting an outstanding education, he attended the University of Oxford where he graduated with a BA in Philosophy, Politics and Economics.

As his cricket career blossomed, he developed a reputation as a playboy in London in the late 1970s.

In 1995, he married Jemima Goldsmith, daughter of businessman James Goldsmith. The couple, who had two sons together, divorced in 2004. A second marriage, to TV journalist Reham Nayyar Khan, also ended in divorce.

His third marriage, to Bushra Bibi, a spiritual leader whom Khan knew during his visits to a 13th-century mausoleum in Pakistan, reflected his deep interest in Sufism—a form of Islamic practice that emphasizes spiritual closeness to God.

Once in power, Khan set about his plan to build a “welfare” state modeled after what he said was an ideal system dating back to the Islamic world some 14 centuries ago.

But his anti-corruption campaign has been roundly criticized as a tool for marginalizing political opponents – many of whom have been jailed for corruption.

Pakistani generals also remained powerful and military officers, both retired and active duty, were given responsibility for more than a dozen civilian enterprises.

[ad_2]