[ad_1]

Year: 1905

Location: Ladyland

They say this is a “feminist utopia,” where the purdah system has been reversed. Here, men are trapped inside, and women roam the world freely, having just stopped war with nonviolent tactics and restored health and progress across nations.

“You need not be afraid to meet a man here. This Ladyland is free from sin and mischief. Virtue itself reigns here.”

Science has advanced far enough that there is an abundance of no-labor farming and flying cars. Scientists, women naturally, have figured out how to trap solar energy and control the weather. No crime, the only religion is truth and love, ideals of peace and coexistence overcome aggression and violence.

In her book Sultana’s Dream (1905) Ruqaiya Sakhwat Hussain created “Lady’s Land” to present an alternative reality – what if men were made to live like women?

The primal science fiction story would become the highlight of the Bengali activist and educator’s work. However, it was only a glimpse of Rukia’s belief that the women – especially Muslims – living in colonial India deserved more than the fate assigned to them.

The feminist intellectual, popularly known as Begum Rukia, drew from her own experience growing up in a conservative home, where her brothers were encouraged to pursue a Western education, while she was held back by being a girl.

Where the woman appears again

Rukia was born into a Bengali Muslim family in Rangpur during the erstwhile Presidency of Bengal in 1880. Her well-to-do family strictly observed Purdah The system – a tradition that separates the sexes and requires women to stay under a complete veil to hide their skin and figure.

Ruqayya was required to learn Urdu only to be able to interpret the Qur’an because it was believed that learning Bengali or English would lead women towards the unfamiliar cultures and “loose morals” of the West. But with her sister, Karimunissa, Ruqayya secretly learned to read and write languages.

Local accounts indicate that luck would never be on Cremonsa’s side – to curb her thirst for knowledge and literature, she married at the age of fourteen. Reportedly, Ruqayya was deeply affected by this sudden end to her sister’s dreams for her future, and this would begin to shape her feminist ideals.

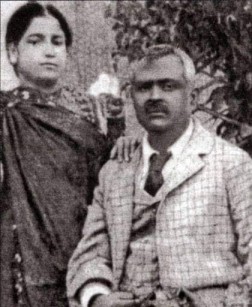

When Ruqayyah was 18, she was married to Khan Bahadur Sakhwat Hussain, a man much older than she was at the time, who was in his forties. But Khan encouraged the young Ruqaiya to pursue her love of education and unbridled literature. On his advice, she adapted Bengali as the primary language in all her later works.

Ruqayya’s literary career began with a Bengali essay titled Bipasa (Thirst) in 1902, followed by a book called Mattichour in 1905.

In the same year, she wrote her most famous work Sultana’s dreamwith herself—reimagined as a woman named Sultana—in the lead.

In the book, Sultana falls asleep “lazily contemplating the state of Indian womanhood”, and wakes up to meet a scientist named Sister Sarah, who takes her around a feminist utopia where women dominate science, history and politics, a vision far removed from the truth to which Sultana is accustomed.

In the book, an all-female university is headed by an “Master Lady”. Before the revolution, her scientific research was considered a “sentimental nightmare” by men for placing more importance on social welfare than “strengthening the military power of the state”.

Perhaps this was inspired by what Rukia observed in the real world, writes Lady Science.

During the colonial period, mobile scientists exploited the imperial expansion of their stores of scientific knowledge, collectively imposing European domination over the rest of the world. The invention of clocks, telescopes, and telegraph machines was driven in part as much by the need for mobility, observation, and communication during war as any civil or scientific need; the legacy of the bomb remains Atomism dominates geopolitics today. Around the world, military budgets continue to rise, while the civil science budgets of many nations are stagnating.”

In 1905, Begum Rukhiya Sakhwat Hussain envisioned a world built by women using science and technology to make everyday life more pleasant and peaceful.

On this Women’s Day, we look to *Sultana’s Dream* as a reminder of how far we’ve come and how far we need to go. pic.twitter.com/0Eo6oP60HI– TaraBooks March 8, 2022

Meanwhile, historical sociologist Mahwa Sarkar writes that Muslim women in colonial India “became invisible”. This was an erased body of nationalist discourse of nationalism and colonial rule in India, and was either confined to the notions of a ‘backward, corrupt minority society’ or ‘completely ignored’.

Project Myopia, an online publication working for historical inclusivity in academia and school curricula, writes that Rokeya’s work was written at a time when education for girls was limited in Bengal, “mostly confined to domestic occupations or specific religious branches”.

For Rokiya, the education of Muslim women was the key to their liberation.

When her husband died suddenly in 1909, this belief led her to establish India’s first school for Muslim girls in his name – the Sakhwat Memorial School for Girls in Bagalpur. For this, she used the 10,000 rupees he had left her, and the remainder she collected from her own resources.

It is said that she went door to door recruiting young girls from families unwilling to allow their daughters an education. Most parents have a condition that Purdah It will be strictly maintained, which is what Rukia has committed to.

The school officially began in 1911 with eight students – a number that slowly increased over time. Keeping her promise to parents, the activist arranged for horse-drawn carriages to ferry the girls to and from school to keep them safe Purdah.

Rukia ran the school, which later moved to Calcutta (now Kolkata) for 24 years, despite strong opposition from the local community. The girls learned lessons in Bengali, English, Urdu, and Persian, as well as activities like physical education, music, cooking, first aid, nursing, and more. Ruqayya personally supervised all school work and was actively involved in teacher training.

Over a century later, the school continues to operate, and is run by the state government.

Where is Ladyland today?

Ruqayya also established Jamiat Anjuman Khawaten-e-Islam, or Islamic Women’s Association, to hold debates and conferences to discuss the status of women’s education.

Meanwhile, her later literary works continued to load her belief in women’s education.

in Padmaraj (1924), told the story of all the working women at Thareni Bhavan, a boarding house and school for ladies. The institution was “revolutionary in its secular approach to education, aiming to provide equal opportunities for local girls regardless of caste, religion or caste”. while, Hackersor The Confined Women (1931), on how to write Purdah It harmed women’s lives and their self-esteem.

Ruqaiya also believed that education was not only a way out of oppression, but also a key to destabilizing colonial rule, religious extremism and sectarianism.

“When any woman tries to raise her head, weapons in the form of religions or scriptures hit her head… Men spread these scriptures as commandments of God to subdue us in the dark… These scriptures are nothing but systems built by men. It will be the words that (we hear) from Males are different if spoken by female saints She once said… that religions only tighten the yoke of slavery around women and justify male domination of women.

She died in 1932, before the creation of both Pakistan and Bangladesh. The latter falls every 9 December as ‘Rukya Day’ and is widely seen as the one that launched a feminist revolution in undivided Bengal. Universities stand in her name and award awards bearing her name to women who demonstrate exceptional achievement.

In the 21st century, “Sultana’s Dream” may seem like a vision that is still very far away. Afterall, Muslim women continue to face stark exclusion from housing, employment and education in India.

But look closely and you’ll find little corners of her dream – women fighting for their rightful place in education, science and politics. So maybe slowly, we’re moving towards our own version of “Ladyland.”

Edited by Yoshita Rao

sources:

Hussain, BRS (2005). Sultana’s dream. India: empty.

Majumdar, R.; (2009). Operations that made Muslim women invisible (review A Visible History, The Disappeared Woman: The Production of Muslim Women in Late Colonial Bengalby M. Sarkar). Economic and political weekly

Feminist visions of science and utopia in “Sultana’s Dream” by Ruqaiya Sakhwat Hussain: Published by Lady Science, 2019

Dream of Sultana and Padmarag (Essence of the Lotus) by Ruqayyah Shakhawat HussainWritten by Ibtisam Ahmed for the Myopia Project

A World Without Manhood in Ruqayyah Sakhwat Husayn: Written by Rafia Zakaria for Fajrpublished on December 13, 2013

Sultana’s Dream: The Brilliant Vision of Ruqia Sakhwat Hussain: By Joshua Glenn for The Wire Science, Posted on April 3, 2022

[ad_2]