[ad_1]

Sarita Devi* (Changing the name), (38), a resident of Mandla in Madhya Pradesh for many years now, has been saving money every month. She planned the daily wager to make sure that every rupee she saves goes into her bank account, all to buy a course for her daughter. She says this money would have helped her get to school on time each day.

She was filled with pride as she diligently opened an account in which to deposit money.

But a few months ago when she went to the bank to check how much money she had accumulated, she had a shock when she realized that her account had been completely wiped out. All that was left was a few hundred rupees.

She was made to realize that because of her illiteracy, like many others, she had also fallen for a scam. Brokers who confirmed to help set up and deal with the account have stolen the funds. She was not alone in this moment of woe—many in the village had experienced it.

It was to change this and much more that District Collector Harshika Singh launched a program to ensure 100 per cent functional literacy in the district.

Talking to India’s bestHarshika says, “These people work hard to make ends meet. It is not fair that their money is stolen just because they are uneducated. To right this wrong, we have introduced adult literacy programmes.”

Freedom from illiteracy

A tribal area that borders Chhattisgarh, Mandala is also a Naxal-influenced area. “Unfortunately, a lot of money was misappropriated from various government schemes that were aimed at the betterment of these tribal communities, especially women, because of various bank frauds. Often because they were asked to put their thumbprint, they didn’t necessarily know what to say ‘yes’ “”.

This resulted in a lot of money being lost, sometimes without a trace. Learning about this scam hit Hersheika and that’s when the idea of having the people of the area “functionally literate” (able to write their names, count, read and write in Hindi) came up with her team. “It became important for us to teach them the basics. Besides being able to sign their name, the program also educated them on how to handle money,” she says.

To elaborate further, she says, “If someone is withdrawing 1,000 rupees, we start by telling them about the different denominations of currency that a teller at a bank might give them.”

“A 2011 survey revealed that the female literacy rate in the region was 56 percent and the overall literacy rate in the region was 68 percent,” she says. With no additional resources at their disposal, Harshika decides to lock up the educated population. She attributes much of the program’s success to that.

Within the same district, the team was able to mobilize 25,000 learner volunteers to advance this program.

However, the programs were not without challenges and hiccups. “The terrain in this area is harsh and organizing a fixed school was difficult. To adapt to this, we have organized these sessions near their homes and even at the work site, where they will learn during their lunch break,” says Harshika.

There were late night private lessons organized for men as well.

Bringing the community together

To ensure the success of this program, the team started by contacting the educated daughters and daughters-in-law of the panchayats. It was they who initiated the hand program and ensured maximum participation. “We wanted it to be a community-driven program. We knew that having an outsider might not work because they wouldn’t understand these women and their dynamics,” she adds.

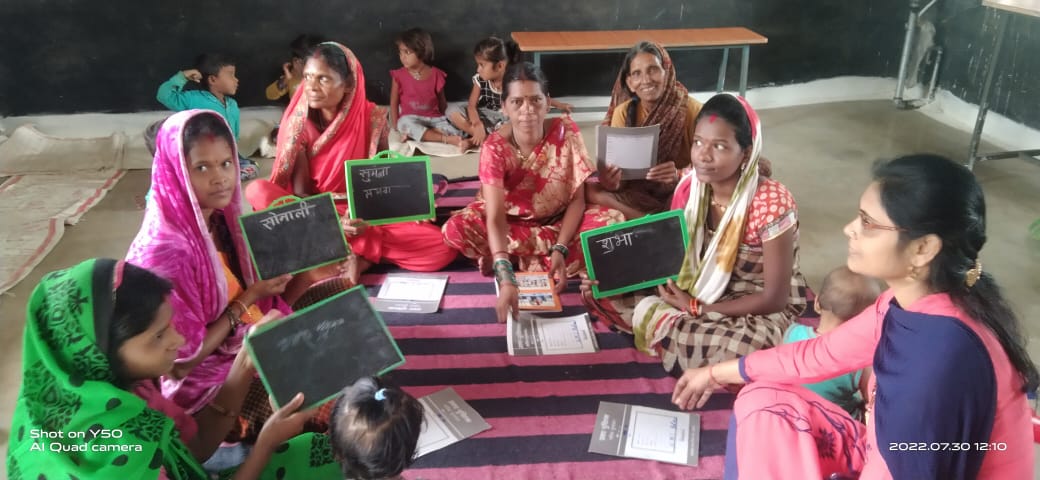

To further this, I simultaneously launched an initiative called GyanDhan. This initiative focused on the crowdsourcing of resources such as books, boards, writing instruments, and all other tools that can be used for teaching. This helped set up Mahela Giannalis (women’s schools) across 490 Gram Panchayats in the district.

Devi Shivanshi, 32, who got married and moved from Chhattisgarh to Mandla, completed her Class 12 education and is now teaching others in the area. She says, “We do two-hour classes every day and sometimes three or four women come and some days many show up. At first, they were also apprehensive about what we were trying to do, but now they understand and appreciate it.”

She continues, “I had the opportunity to study and it made a huge difference in the way I think. This is the change I want to bring to these women as well.”

Kanwaljit Marari (26), an English graduate student from Mandla City who teaches computer literacy and is associated with the teaching programme, says, “I come from an educated family and have seen what a difference it makes in one’s thought process. I had the honor of having On education and when I came to this area, where my family resides, I was shocked to see the poor level of illiteracy.”

She continues, “I found women very naive and naïve – they considered themselves inferior. I decided to try and change that mindset. I’m doing this without any paycheck. It’s completely voluntary.”

On the experience of teaching these women, Kanwaljit says that while the first few days were challenging and left her feeling very frustrated, the women were fast learners and kept coming to class with a burning desire to learn well. “I have often heard men say that women are naturally ’emotional fools.’ I wanted to work on erasing that notion,” adds Kanwaljit.

Empowering women, one alphabet at a time

While volunteers work hard to ensure that the program is accessible and understood by all, it’s students like Sunita Marco who succeed. The 40-year-old says she hasn’t been to school before that, and can’t even say for sure if she’s already 40. I wanted to be able to sign my name just like I’ve seen others do,” she says.

Sunita takes up to two hours every day to go to the center and learn. She remembers the first day she entered the center and says, “The first day I learned the alphabet I felt like they were dancing before me. It took me a while but now when I’m able to read I feel this sense of accomplishment.” Sunita’s children, two girls and two boys, are also very proud of what their mother has achieved. “I’m not Anjutha chap (Mom) anymore,” she adds, a glint in her eyes.

To encourage more women to go out and learn, Harshika says whenever there is an official function in the area, the most literate women from the village are invited to be the main guests.

“Be it a school-wide celebration or even a celebration of Independence and Republic Day, these women were always invited to be the main person. This brought them a lot of social respect and encouraged others as well.

For Harshika, there have been several moments of joy since this program was implemented. “I remember meeting an 80-year-old lady at Gram Panchayat who took the time to write me a letter thanking me for starting this program. She was one of the beneficiaries of the program and said that although she had heard her name called her whole life, the ability to read and write had enabled her to do so.”

Biggest win for Harshika Comes when you see the number of reductions in reported bank fraud cases in its area. “That was the whole reason we started this program. To protect the hard-earned money of everyone in my area. That’s our real reward.”

All photos provided by: Harshika Singh

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

[ad_2]