[ad_1]

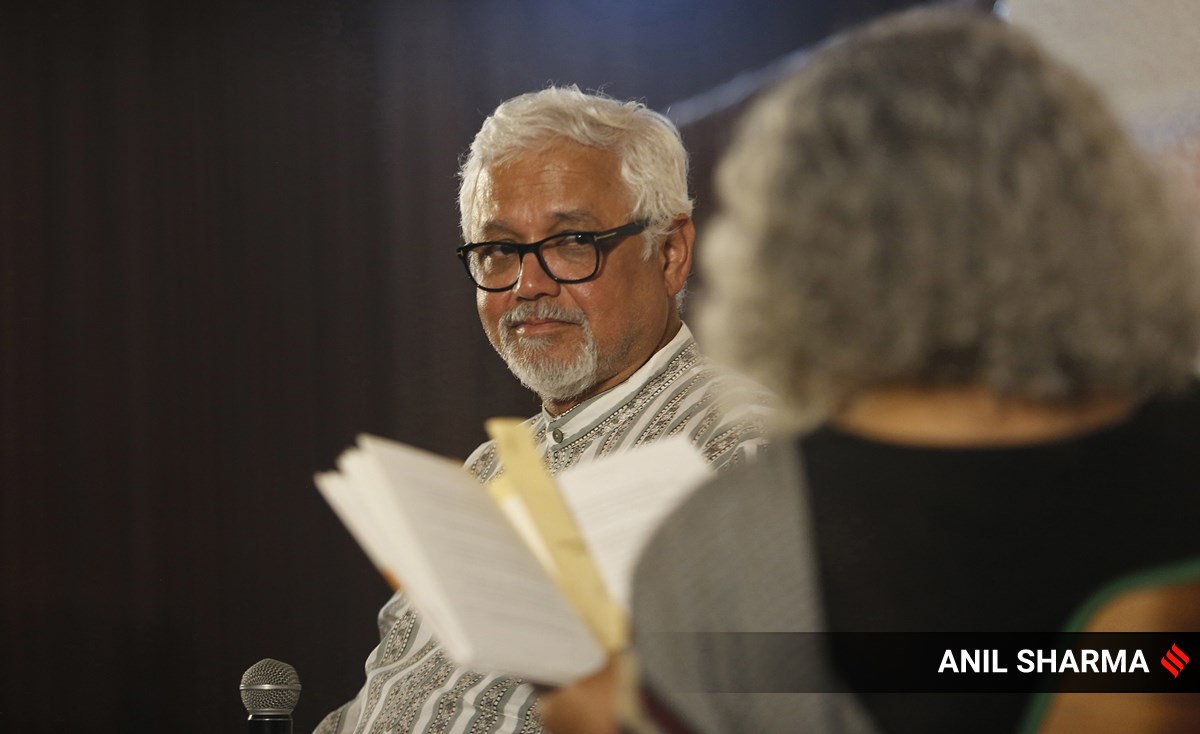

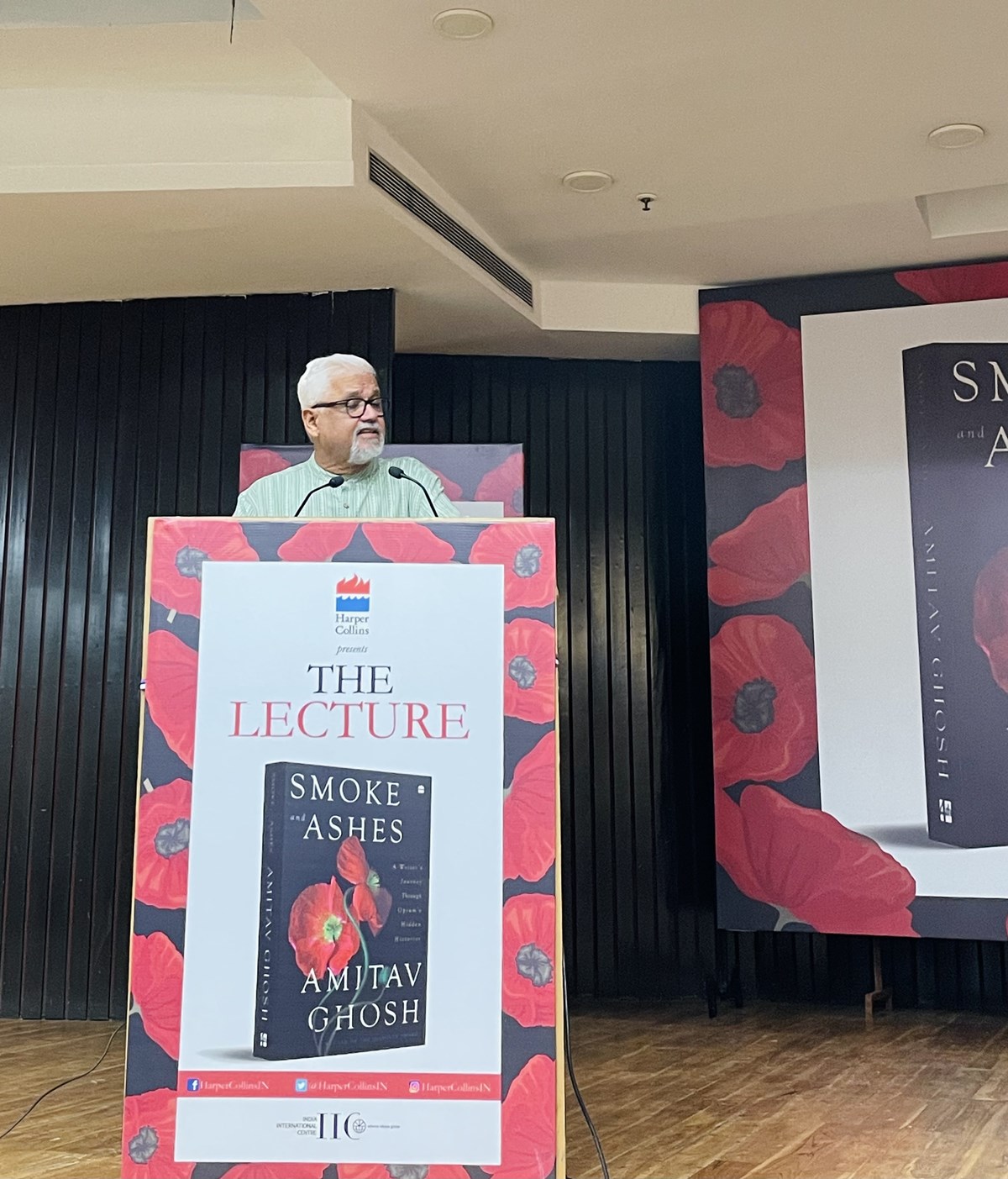

Last week, at the India International Center on Saturday night, amid stormy skies and a flooded city, award-winning author Jnanpith Amitav Ghosh, announced the conclusion of his 20-year academic affair with the opium poppy and its bloody seeds strewn across the pages of The World. History: “It is a deeply depressing story about human fragility and vulnerability. We like to say that we are the masters of our own destiny, but with this story, you see that this humble and simple flower has outshone us at every turn,” said Ghosh, who was in conversation with print editor Shekhar Gupta on the occasion of the launch of his latest book, Smoke and ash (Rs. 699, HarperCollins), a non-fiction work about the history of opium and its unacknowledged impact on the world order.

Ghosh’s intellectual curiosity about the plant sparked the search period for the hugely popular Ibis Trilogy, a story about laborers near the Indian Ocean before the first Opium War in the 19th century between Britain and China – caused by illegal sales of Indian lands to China despite a ban. The Qing found that their institutions were collapsing due to the influx of opium and it was necessary to control it. The British, for whom it was “the most valuable commodity produced by weight” at the time, according to Ghosh, demanded free trade instead. declared war.

Smoke and Ashes delves into the story of the opium poppy and how the British cultivated huge amounts of it on Indian soil. (Anil Sharma snapshot)

Smoke and Ashes delves into the story of the opium poppy and how the British cultivated huge amounts of it on Indian soil. (Anil Sharma snapshot)

“Europeans started calling the Chinese irredeemably corrupt and idiots (when their institutions began to fail because of opium)… It happened to all of us. Opium has this ability to undermine state structures. It happens in Mexico, America and even India… Once these addictive substances create these amazing markets, they are almost impossible to control,” Ghosh said.

Smoke and Ashes delves into the story of the opium poppy and how the British cultivated huge amounts of it on Indian soil. In the 16th century, there was already a small industry in Patna and Malwa district for medicinal uses. After the Battle of Buxar in the 18th century, Bihar came under the control of the British – and so began exports to China in exchange for tea. Ghosh said, “The market grew at an enormous rate, production within Bihar expanded over a very small period… By 1799, the British declared a complete monopoly on production and established the Opium Department.”

It was this opium section that appeared in the Ibis trilogy as well, its central story anchored by the workers who cultivated the plant for British use. “The department had incredible powers like criminalizing farmers, imprisoning anyone, and the police… They had incredible quotas for farmers every year, who produce opium below cost,” Ghosh said.

Ghosh referred to the way the sepoys of Purvanchal (eastern Uttar Pradesh) revolted in 1857 because they came from a region of exploited farmers and how “large parts of London” were built on “opium money” produced in factories such as the one in Gazipur. . , “Opium has played such a foundational role in the history and society of India. There is a lot of historical work on the subject, but did we read about it in school? No. There is a disavowal of it. It is important for us to learn about it.”

A day earlier, Ghosh had been in conversation with poet Sukrita Paul at the Kiran Nadar Art Museum, about a similar denial. Quietly expressed rages at pent-up knowledge and oppressed cultures are echoed, though this time mobilized not over a plant, but an entire ecosystem—an ecosystem akin to Ghosh’s literary world: the Sundarbans.

“When I went there in 2000, it opened my eyes to climate change. We were skeptical at the time. But you could see what was unfolding. The loss of biodiversity was massive,” he said, adding that crabs, which aerate the soil for the survival of the mangrove forest, have seen a significant decline over the past two decades.

Ghosh also cited the legend of Bun Bibi, the forest spirit of the Sundarbans forest, which he retold in his 2021 graphic novel Jungle Namma (Rs. 699, 4th Estate), illustrated by Salman Toor. He mentioned how both Muslims and Hindus (including Dalits) worshiped the soul, and it “comes from the earth” rather than religion.

Book launch (credits: HarperCollins)

Book launch (credits: HarperCollins)

Upon recent visits, Ghosh claims to have seen depleted bird life, plastic and light pollution, methanol seeping into the river, and devastating cyclones, adding that the story of Manasa Devi, the Hindu snake goddess, captures the dynamics of climate change with “absolute accuracy.”

“She is understood to be a serpent goddess but she is a goddess of many things, of weather, of storms, of floods… She gives voice to all natural phenomena. She understands that someone has to give voice to non-humans. And she doesn’t command the creatures – she negotiates with the snakes in the story.”

“Donna Merchant represents the principle of profit,” he added. “Manasa Devi tries to restrain and drive him away but in the end he is allowed to return when he accepts her supremacy. It is the conflict between profit motive and non-human needs.”

[ad_2]